After spending the past two days researching the Christmas carol “Gaudete,” two things are clear: 1) This is a really popular carol, and 2) Everyone thinks it’s medieval. Well, I Kathryn of Jersey, First of My Name, Mother of Hound Dogs, Burster of Bubbles, am here to disappoint you. “Gaudete” is solidly Early Modern.

Many people, myself included, probably came to know the carol through the 1972 Steeleye Span recording of it. It was their first hit single, and one of the only songs by a progressive folk group to become a hit single.

It has a jaunty “days of yore” sound, doesn’t it? Well, all yores are not alike! I’ll tell you where it’s really from, and then explain some of the reasons that I think we believe it to be and hear it as medieval.

“Gaudete” comes to us from a 16th century Finnish songbook, Piae cantiones. In 1853, John Mason Neale (the guy who wrote “Good King Wenceslas”) received a copy and then published his own editions of the songs, introducing the carols to England, right as the Christmas revival was gaining steam. Many more collections of “ancient and new” Christmas carols followed, and the “ancient”ness of the older carols was often overestimated.

The songs in Piae cantiones come from the 15th and 16th centuries. (It was printed in 1582.) Songs from the 15th century, especially the first half, can be considered medieval. So in that, it’s fair to say that Piae is a collection of medieval carols, but only in part. There are some major stylistic changes in the 16th century, which is why we call it the Early Modern period—that’s when a lot of things that we use now (Modern English, our current musical notation, etc) came into use.

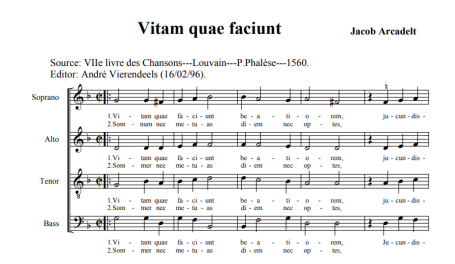

“Gaudete” is actually a Latin chanson by the 16th century Humanist composer Arcadelt, called Vitam quae faciunt, which in turn is based on a setting of the same poem from twenty years earlier, by Senfl. But you don’t have to take my word for it! See for yourselves:

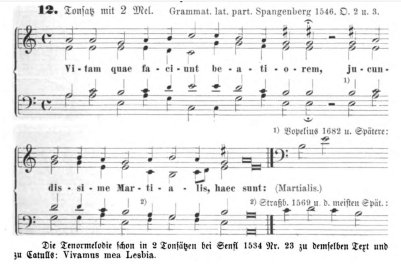

Senfl, Vitam quae faciunt (1534; modern transcription).

Arcadelt (1556; modern transcription)

Anonymous, “Gaudete” (1582)

Apart from there being no earlier sources to contradict this timeline, there are mentions in the following century of “Gaudete” being sung to the tune of Vitam quae faciunt.

In his 1910 edition of Piae cantiones, Woodward incorrectly assumes that the song has a cantus firmus (meaning that it’s based on a plainchant), as medieval motets (Latin songs) were. Arcadelt does base his work on an existing tenor, but not a chant—the tenor of Senfl’s setting. (The same tenor part became the melody of a Lutheran hymn, “Danket dem Herren,” which J.S. Bach later made into a chorale.)

I am not 100% sure whether Senfl took his tenor from somewhere else, but it appears to be his own composition. As for the lyrics of “Gaudete,” all signs point to them being contemporary. Someone just took Vitam quae faciunt and wrote new words for it.

So, the song is quite firmly rooted in the 16th century—which is still pretty old, let’s be reasonable—but there are some historical reasons it picked up a reputation as being medieval:

- It’s in a book that does contain (late) medieval carols. [1]

- Musicology was a new field in the 19th century and historians at that time simply didn’t know as much about the stylistic traits of medieval music.

- It’s in Latin, which is pretty Old Timey and made an early historian mistake it for an older genre of music, a motet.

- For numerous reasons, 19th century historians tended to over-hype things as medieval or “ancient.” Creating a sense of cultural continuity back to the Middle Ages gave nationalists political ammo, basically.

- Below the Salt, the Steeleye Span album that the song appears on, has cover art depicting a medieval feast, with a medieval font. The power of suggestion shouldn’t be underestimated.

Now, what about some of the musical reasons?

I’ve actually brought up “Gaudete” before (in the post I just linked above), and you’ll note that I said the tune sounded much older than 16th century. I, too, was hoodwinked! But there are a few reasons to hear it as older.

First of all, Arcadelt didn’t just take Senfl’s tenor, he borrowed liberally from the soprano and bass. I have seen credible sources claim that the tune is a 15th or 16th century folk song. If that’s the case, then the tune could indeed be a bit older than the 15th century. I haven’t yet found any proof of this (said sources gave no citations). So let’s just get that out of the way—it is within the realm of possibility that Senfl quoted a known song of unknown age. But folk song or no, we’re still working in the realm of the Early Modern period.

Let’s compare to another of Arcadelt’s Latin songs, At trepida.

As different as At trepida sounds, if you speed up the playback, you might note some rhythmic similarities in places. It’s that lilting, syncopated trochaic rhythm in “Gaudete” that makes it sound medieval-ish, to me. It’s close, but not quite the same, if you compare it to earlier music:

Or the famous round, “Sumer is icumen in”:

It turns out that there’s a good reason to hear some rhythmic similarities! As an early humanist, Arcadelt—and his Latin songs, in particular—were in keeping with certain neo-Platonic notions about music. (Platonic and Aristotelian ideas also guided many medieval theorists.) The most well-known of these ideas is the doctrine of the affections, which posit that the key/mode of a piece of music has physical and moral influence over the listener.

As Kate van Orden explains in her wonderful article, “Les Vers lascifs d’Horace: Arcadelt’s Latin Chansons,” these classical doctrines encompassed all aspects of music, including meter, which in Ancient Greece and the early Middle Ages was tied to poetic meter. Medieval rhythmic modes, which were based on classical poetic meters, are a defining feature of polyphonic music in the 13th century. You can hear the trochaic feet quite clearly in the above examples, as in “Gaudete.”

In the 16th century, humanist composers returned to an emphasis on poetic meter in their text settings. Arcadelt’s Latin songs are especially metrical and repetitive, in keeping with their source poetry, which sometimes creates a dance-like character. This metricity works well with the textual punchiness (more accented delivery) that was in fashion for French music at the time. (Arcadelt wrote his Latin songs while employed at a French court.)

Lastly, one of the harmonic features of “Gaudete,” and Arcadelt’s other Latin songs, is parallel thirds and sixths. Parallel intervals are one of the distinctive qualities of early medieval music. Early medieval music uses perfect intervals (fourths, fifths, and octaves), never thirds or sixths, but it’s perfectly reasonable for a lay person to hear continuous parallel intervals and be reminded of medieval music. It’s a striking sound, and it’s something that’s common in 16th century harmony (as you can hear in the link below), but dies out after about 1600. So, if you hear that kind of close harmony as old, you’re right.

To review the musical reasons we might hear “Gaudete” as medieval:

- Its punchy, metrical quality.

- It uses the same classical poetic meters as medieval music.

- Parallel intervals.

- The chord in the final cadence doesn’t have a third, which is old-fashioned.

I made the caveat that “Gaudete”‘s tune could, conceivably, have roots in earlier centuries. I said this because we are not omniscient, I am not an expert in Early Modern carols, and I have to allow for the possibility. But if you listen to other upbeat songs from the 1530s-1550s, you’ll hear a lot of similarities with “Gaudete.” For example:

So, beware wishful thinking! Even knowing that the harmonic language of “Gaudete” was definitely not medieval, the distinctive meter tickled a memory of 13th century song and confused me, at first. However, when you hear it in the context of other music of its time, “Gaudete” fits in quite clearly, I think.

- You might ask, “Well how do you know they didn’t exist before and weren’t written down?” That can definitely be the case at times. However, stylistic criteria can often rule that out. Even if a melody had existed in, say, 1200, rhythmic and harmonic conventions changed so much between then and 1550 that any composition based on that melody usually has very little in common with the original. The process of modernizing music isn’t quite like building onto a house. You don’t always retain the original character—it becomes a wholly new thing, like a tadpole growing into a frog.

Leave a comment